Flotsam – July

British Nuclear Submarines Threatened by Cyber Attacks

At the beginning of June, the British American Security Information Council (BASIC) published an article entitled “Hacking UK Trident: A Growing Threat”. This article deals with the growing threat posed by cyber attacks on the numerous computer systems aboard the four British submarines with ballistic missiles (SSBN) of the Vanguard class and their infrastructure.

BASIC is a small London-based think tank whose ultimate goal and vision is to free the world from the nuclear threat. In a particularly dialogue-based approach, the recognised non-profit organisation advocates nuclear disarmament and would like to promote political and social discourse on this topic above all through trustworthy information and thus contribute to creative, new solutions to the complex security policy problems.

The media response to the publication of this article should further enhance existing security concerns about the computer systems of the British SSBNs reported in the stranded property in December 2016. In a BBC-Interview on 15 May, British Defence Secretary Sir Michael Fallon confirmed that the isolated British Vanguard boats were fully protected against cyber attacks and that he had full confidence in the British nuclear deterrent. He did not want to answer the question of whether the Vanguard class booths still run Windows XP, referring to security concerns, although a number of more detailed information about it has already been published.

The Vanguard class submarines, as already described in Flotsam July 2016, are designed to use to ensure the nuclear second strike capability of Great Britain with their Trident missiles. The prospect of a devastating retaliation strike from an ideally undiscovered Trident boat operating in the middle of the ocean is intended to deter a potential attacker from a nuclear first strike. In order to maintain the second strike capability, the Royal Navy, unlike the US Navy or the Russian Navy, goes so far as to leave the crews the possibility of launching the nuclear missiles on their own initiative and without further authorization from the gouvernment. For the event of a nuclear first strike disabling the top British leadership, each of the four British SSBNs has a letter of last resort from the current British Prime Minister stored in a special vault. This handwritten letter contains instructions on how the commander should behave in this case, especially if he should press the nuclear trigger, which was modeled after a Colt Peacemaker revolver on Vanguard-class boats.

The concentration of the entire British nuclear force on the one of its SSBNs, which is currently on patrol to maintain nuclear deterrence, makes it a particularly rewarding target for an opponent. Its localization or limitation of the submarine’s capabilities would promise considerable strategic advantages for an opponent, not to mention a complete neutralization of the boat and thus the British second strike capability.

In their article, the experts at BASIC assume that the cyber threat can only come from other countries. No secret sources were used in the creation of the article, but only published or whistleblowed ones. Terrorists would probably prefer more easily achievable targets with more publicity than the Trident weapon system. According to the authors, private hackers, hacktivists and cybercriminals would not have the necessary know-how and, above all, the necessary resources to carry out a complex operation on such a large scale as intrusion into the trident weapon system. Only other nuclear competing states, which are not mentioned by name in the whole article, would have both the pronounced motivation and the necessary financial and especially intelligence resources to try to gain a considerable strategic advantage by hacking the Trident weapon system.

In their article, the authors sketch out many possible ways in which cyber attackers could gain access to the computer systems of the Vanguard submarines.

The Isolated Systems – Air Gap

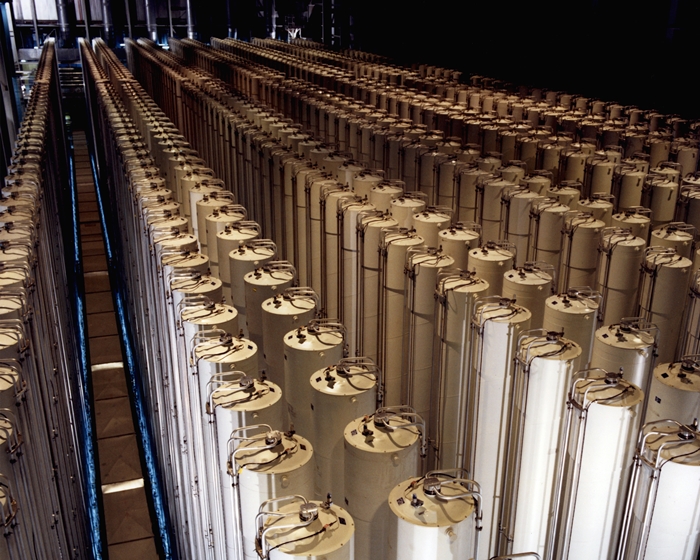

The computer systems of a Vanguard submarine on patrol are not logically or physically connected to any other computer system or network, which in this case appears to be particularly obvious. But the article strongly contradicts the view of the British Ministry of Defence that this fact alone confers a higher level of security against cyber attacks on the systems alone. In order for these highly complex computer systems to function optimally at all times, it would inevitably be necessary to exchange user data between these and other systems at least temporarily. The physical separation, known as an Air Gap in computer science, is overcome by some form of data storage medium. However, this storage medium could also be used to transmit malware to the submarines if, for example, cyber attackers were able to infiltrate one of the source systems of the user data, e. g. of a civilian subcontractor. The prominent malware Stuxnet is one example of this. This highly developed computer worm interfered with the operation of the Iranian uranium enrichment plant in Natanz in 2010 by manipulating the computer control of the electric motors of the gas centrifuges there. Stuxnet entered these otherwise completely isolated computer systems via special notebooks and, after its discovery, made the danger of cyber attacks on special infrastructure or industry clear to the world’s public.

The Human Factor – Social Engineering

Through targeted interpersonal influencing of individuals who have access to targeted computer systems, while attempting to compromise these cyberattackers can usually achieve results more effectively and quickly than with purely technical methods alone. For this method – also known as social engineering – a target is initially spied on in order to be able to manipulate it later on by exploiting its weaknesses.

One form of social engineering is phishing, in which fake websites, e-mails, any form of short messages or other means of communication are used to deceive the target person and thus mislead them into revealing personal data, primarily passwords or the like. Phishing is usually directed against a group of people, but when cyber attackers focus their efforts on a single person, it is called spear phishing.

It is assumed that around 80% of the world’s cyberattacks are carried out using these two methods, which only exploit human weaknesses, so the authors of the article believe it is highly likely that cyber attackers of the Vanguard submarines would also target humans as the weakest link in this highly complex system. Target persons do not necessarily have to be members of the submarine crew, even persons at the base, in the staffs or from private subcontractors could – with or without their knowledge – allow attackers to penetrate the system.

Attacks using social engineering are generally difficult to repel. All possible targets who have to work with a system must always have a high security awareness, without being so suspicious that the cooperation suffers from it. The revelations of the British whistleblower William McNeilly in 2015 gave rise to considerable doubts at the time about the general safety awareness of the staff working around the Vanguard boats. In a 19-page report published online, he mentions numerous grievances on the British SSBNs and in their environment. As far as security is concerned, he argues that it is more difficult to get into most London nightclubs than into a vanguard submarine´s control room. McNeilly was dishonorably dismissed from the Royal Navy for his publications, but otherwise not prosecuted.

Small Cause – Great Effect

With the help of many witness reports and other documents in the U-boat Archive, it is possible to understand very clearly how important it is that every member of the crew of a U-boat on board performs its special duty correctly at all times. Even seemingly minor operating errors of the complex machinery of a U-boat during the Second World War could have serious consequences, including the loss of the boat. In addition, numerous examples can be found of how the failure of a subsystem, which at first glance appears insignificant, has reduced, if not even ruined the operational readiness of a boat.

On board all modern submarines, including the Vanguard class, all critical systems are digitally automated. If you want to transfer the experiences of German submarines of the Second World War to the modern nuclear submarines of the Royal Navy, you would have to state that it is important that every member of the crew of a submarine performs its special duty at any time correctly on and with its internal network client – its computer. Even displaying incorrect data in a subsystem such as propulsion or reactor control or navigating through malicious programs could ultimately result in a potentially serious restriction of the submarine’s operational readiness and thus of the UK’s Secondary Strike capability. If one considers the failed missile test of a Vanguard submarine, which is reported in the Flotsam of January 2017, as a possible practical manifestation of a successful cyber attack, it becomes clear how an attack on just one single subsystem, in this case the missile control system, could render the entire weapon system SSBN worthless in the end. However, it does not seem particularly opportune for a potential cyber attacker to activate his previously undetected malware already while testing a weapon system, as this would expose him to a higher detection risk. Insofar, it can almost be ruled out that the mistaken missile test was indeed a cyber attack.

The authors of the article work through a wealth of submarine systems with regard to their risk of becoming subects to cyber attacks, but without being so specific that potential cyber attackers could only gain the slightest advantage. In particular, they also look at a cyber-threat, which they call Advanced Persistent Threat. Malicious programs are injected into the systems of a boat at the earliest possible stage, possibly already during the development or construction phase, in order to hide themselves there until they are activated, possibly a long time later. This activation does not necessarily have to be carried out externally, but could also be triggered by certain events in the computer systems themselves.

Conclusion

In the Flotsam Issue of December 2016, the only risk that could be all-cleared was the choice of the operating system for the British Vanguard class submarines. The risks described in the “Hacking Trident” article are therefore also present for all conceivable operating systems. Even with the greatest effort, these risks can only be minimized, but never eliminated completely. The absolute security of the computer systems of the Vanguard boats and their Trident missiles, which the British Minister of Defence has just called for, cannot be guaranteed just by their isolation. No system is really safe or will ever be. Therefore, these cyber risks, which are ultimately unavoidable, should be clearly outlined, as should other risks. Only then could these risks be weighed against the assumed benefits of the British nuclear weapons in an appropriate social discourse. Since Britain is the only nuclear power that relies solely on submarine-based nuclear missiles, the debate on British nuclear weapons is necessarily also a debate about submarines and as such is being followed with interest at the German U-boat Museum – also for our readers.

Weblinks:

the cyber threat:

- https://www.basicint.org/sites/default/files/HACKING_UK_TRIDENT.pdf

- https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2017/jun/01/uks-trident-nuclear-submarines-vulnerable-to-catastrophic-hack-cyber-attack

- https://rusi.org/sites/default/files/cyber_threats_and_nuclear_combined.1.pdf

- https://www.europeanleadershipnetwork.org/medialibrary/2016/02/04/d2106a19/Is%20Trident%20safe%20from%20cyber%20attack.pdf

Stuxnet:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stuxnet

- https://www.symantec.com/content/en/us/enterprise/media/security_response/whitepapers/w32_stuxnet_dossier.pdf

the whistleblower William McNeilly:

- https://nuclearinfo.org/sites/default/files/William%20McNeilly%20Secret%20Nuclear%20Threat%20120515.pdf

- https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2015/jun/17/trident-whistleblower-william-mcneilly-discharged-from-royal-navy